English available languages

English available languages

The referendum held in the United Kingdom on 23 June 2016 on the question of whether to remain in, or leave, the European Union resulted in 51.9% of those voting (on a 71.8% turn-out) supporting withdrawal from the Union. Although, formally speaking, the referendum was consultative, the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, and his government had indicated clearly in advance that the outcome would be considered binding. In announcing his resignation, Cameron said that the UK would activate the procedure set out in Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) enabling a Member State to withdraw, but that this process would wait until his successor had been chosen (by October). In a resolution adopted at the conclusion of a special plenary session on 28 June, MEPs called on the UK government to instigate ‘a swift and coherent implementation of the withdrawal procedure’, to prevent ‘damaging uncertainty for everyone and to protect the Union’s integrity’.

Article 50 procedure

The right of a Member State to withdraw from the European Union was introduced explicitly by the Lisbon Treaty. Article 50 TEU now sets out the procedure for withdrawal. There is no precedent in EU history of a Member State withdrawing.

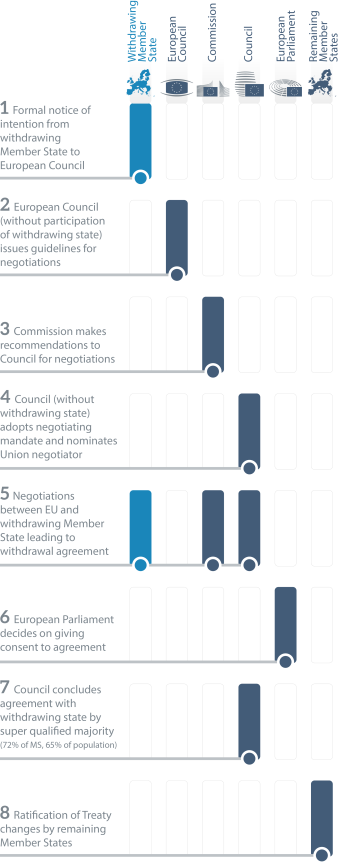

The formal withdrawal process is initiated by a notification from the Member State wishing to withdraw to the European Council, declaring its intention to do so. Article 50 does not, however, specify what form this notification should take. Whilst the timing of this notification is in the hands of the Member State concerned, and informal discussions could take place between it and other Member States and/or EU institutions prior to the notification, any negotiations need to observe the Article 50 procedure, with the involvement of the actors as determined by this provision.

The European Council (without the participation of the Member State concerned) provides guidelines for the negotiations between the EU and the state concerned, and the Council adopts the negotiating mandate and nominates the Union negotiator. As a general rule, the European Commission negotiates agreements with third countries on behalf of the EU (Article 218(3) TFEU), but in the case of a withdrawal agreement, the Treaties leave it open for the Council to nominate a different Union negotiator. In any case, the Council would establish a special committee to oversee the negotiations.

Negotiations on a withdrawal agreement

The European Union and the withdrawing Member State have a time-frame of two years to agree on withdrawal arrangements. After that, membership ends automatically (with or without a withdrawal agreement), unless the European Council (by consensus) and the Member State concerned decide to extend this period (Article 50(3) TEU). The withdrawal agreement could set out concrete arrangements relating, inter alia, to institutional and budgetary matters, and the future status of EU citizens in the withdrawing state and its citizens in other Member States. The agreement might also include provisions on the departing Member State’s future relationship with the Union, or these details could be left to a separate agreement, to be negotiated either in parallel or after the state’s formal exit. In particular, this second aspect is seen by experts as potentially very complex and could require negotiations taking much longer than the two-year period.

The European Union and the withdrawing Member State have a time-frame of two years to agree on withdrawal arrangements. After that, membership ends automatically (with or without a withdrawal agreement), unless the European Council (by consensus) and the Member State concerned decide to extend this period (Article 50(3) TEU). The withdrawal agreement could set out concrete arrangements relating, inter alia, to institutional and budgetary matters, and the future status of EU citizens in the withdrawing state and its citizens in other Member States. The agreement might also include provisions on the departing Member State’s future relationship with the Union, or these details could be left to a separate agreement, to be negotiated either in parallel or after the state’s formal exit. In particular, this second aspect is seen by experts as potentially very complex and could require negotiations taking much longer than the two-year period.

Before concluding the withdrawal agreement, the Council needs to obtain the European Parliament’s consent (Article 50(2) TEU), voting by a simple majority of the votes cast. Whilst the Parliament has no formal role within the negotiation process, other than the right to receive regular information on its progress, its right to withhold consent to the final agreement offers political leverage to influence the agreement.

Under Article 50(4) TEU, the member of the European Council or of the Council representing the withdrawing Member State does not participate in the discussions of the two institutions or in decisions concerning the withdrawal. However, no similar provision exists for MEPs elected in the withdrawing Member State, so that they could still participate in debates in the Parliament and in its committees, and in voting on Parliament’s decision on giving or not consent to the withdrawal agreement.

Finalizing the withdrawal

The Council takes the decision to conclude the withdrawal agreement by a ‘super qualified majority‘, without the participation of the state concerned. The qualified majority is defined in this case as at least 72% of the members of the Council (20 out of 27 Member States), comprising at least 65% of the population of the remaining Member States (at present, at least 288 million of the 444 million population of the 27 remaining Member States).

The withdrawal of a Member State does not require ratification by the remaining Member States – Article 50(1) TEU mentions (in a declaratory way) only the decision of the withdrawing state, in accordance with its constitutional requirements. However, any Treaty changes that might be necessary as a consequence of the withdrawal would need to be ratified by the remaining Member States, in accordance with Article 48 TEU. At the very least, Article 52 TEU on the territorial scope of the Treaties, which lists the Member States, would need to be amended, and Protocols concerning the withdrawing Member State revised or repealed. Moreover, any international agreement on the future relationship with the withdrawing state, unless limited to matters falling under exclusive EU competence, would require ratification following the national procedures of the remaining Member States.

Under Article 50(3) TEU, the legal consequence of a withdrawal from the EU is the end of the application of the Treaties and the Protocols thereto in the state concerned from that point on.

Until the date of its actual withdrawal from the EU, the representatives of the withdrawing state in the Council and European Council would continue to take part in the adoption of all EU acts other than those relating to the withdrawal. Moreover, the withdrawing state would remain bound by EU law and its commitments there under until that date.

Source: EPTT

English available languages

English available languages